If there’s one thing I’ve learned, Czech people are PROUD of their bread. There are many different types. With the advent of convenience culture, though, people are starting to mourn the quality of loaves which are sold in the supermarket (both links Czech only). Still, all things considered, it’s light years ahead of the “fresh” bread and especially the packaged bread you can get in American supermarkets.

I never much liked bread til it was metaphorically crammed down my throat while eating goulash or schnitzel (Czech meals must have a side, the point of which is to balance the oily meat or sauce and buff up the meal).

As Isabel at The Sunny Side of This writes of her Slovenian husband,

In Mexico dinner is usually a bowl of cereal, a salad or a quesadilla. […] Which is “too heavy” for Slovenian guys. Their version of light is half a baguette or loaf of bread with dozens slices of cheeses and hams (oh, and beer!). I laughed so much when a friend told me that her Slovenian boyfriend refuses to have potatoes, and chicken for dinner. But it’s totally okay with having half a kilo worth of sandwiches for himself. Maybe their version of “light” is something that doesn’t need to be cooked? Anyway, I’m giving you the heads up for when you encounter this inevitable cultural clash.

I also have never gotten used to the idea of having just bread with sádlo or škvarky, or topinka – sort of like fried toast? – for dinner. I’m American, dammit! Lunch might be the main meal in CZ, but in Amurrica it’s dinner.

A Very Scientific Case Study in Bread

Exhibit A: Comparing Google results

When you Google image “bread,” you will see:

This may be due to the prominence of the idiom “the greatest thing since sliced bread!” which refers to pre-sliced bread (perfected between 1912-1928) as a miracle invention for the modern age. Living in CZ, though, I realize that this actually hurts the freshness and quality and it’s much better to have your own bread box (really!) and slicer at home, as many Czechs do.

Meanwhile, when you Google image “chleba,” you will see:

Hmm… interesting. Very interesting. *rubs invisible beard*

Bread (chleba) vs. Pastry (pečivo)

To understand my perspective, you have to look at what is considered rohlík in the Czech search. That can be translated as “roll,” and is the only thing which is considered a roll. Meanwhile, and I don’t know if it’s just me, if you look at the American search, you can see in the pictures with the basket and the many bowls that bread is grouped together with what I’d also call rolls (part of a subcategory of bread and/or pastries). I have been told I was crazy for calling, for example, Kaiser rolls (yes, kaiserky are called rolls in English) bread. But I eat it with sliced meat, cheese or butter, so it serves the same function!

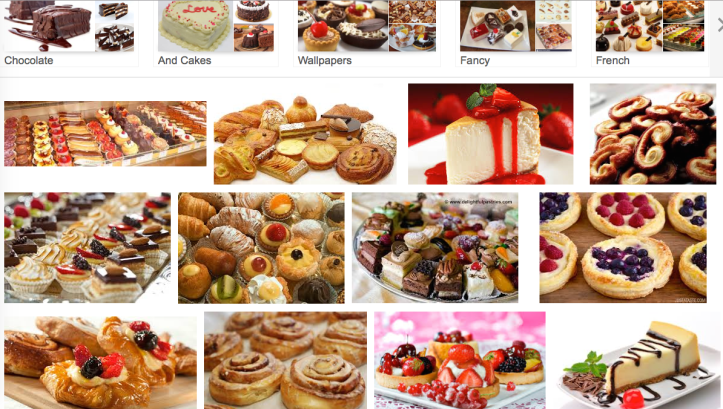

So to be fair, a pastry is a much wider category than it is in Czech and can be salty or sweet. Examples: apple strudel (which would not be considered a pastry in Czech) or my grandma’s favorite, the danish.

Pastry:

Pečiva:

You can clearly see that the American “pastry” slants towards sweetness (while the Czech “pečivo” is less obviously so) and is easily connected with cake, Frenchness or fanciness. Many Czech pastries are sweet, but many are also bread-like and neutral.

Cake (dort, buchta) vs. Pie (?)

My friend Klára wonders why we have such confusing ways of talking about certain pastries (and here I mean all bread and cake-like things). For example, banana bread.

The translations for cake and pie in Czech are much less accurate or one-to-one than bread vs. pastry. While dort pretty clearly means cake, it took two years for me to gain even a simple understanding of the difference between buchta (which I would sometimes identify as cake in English) and koláč.

In the basic, traditional Czech sense, I thought buchta was a fluffy square that had to have filling, while koláč was sort of a fruit-filled pizza pie-looking…pie… (help!).

Buchta on the left and koláč on the right, from ApetitOnline.cz and Pinterest, respectively.

Good old Wikipedia: “Buchteln are sweet rolls made of yeast dough, filled with jam, ground poppy seeds or curd and baked in a large pan so that they stick together. The traditional Buchtel is filled with plum Powidl [Czech, povidla] jam. Buchteln are topped with vanilla sauce, powdered sugar or eaten plain and warm. Buchteln are served mostly as a dessert but can also be used as a main dish.”

Czech idiom alert! I love how buchty can be slang for “abs” based on the way they look together on the pan.

“A Kolach is a type of pastry that holds a dollop of fruit, rimmed by a puffy pillow of supple dough. Originating as a semisweet wedding dessert from Central Europe, they have become popular in parts of the United States.”

Czech idiom alert! Bez práce nejsou koláče. Translation: Without work, there are no “kolaches.” Meaning: You can’t make accomplish anything without hard work.

No exact thing as pie exists in CZ, but koláč or frgál is sometimes translated as pie because they are the most similar things.

Pie, meanwhile, can be flat in the pizza sense, but is always raised and with a crust in the sweet dessert sense. Here are three examples of American pies – apple (from Venngage), pecan (from NY Times) and pumpkin pie (from Food Network) respectively. Let your mouth water freely.

The confusing thing is that while buchta and koláč are both somewhat sweet, neither has to be considered dessert. Sometimes, they’re even served as a main meal and option for sweet lunch! Since Czechs are very good bakers and like to always have something around for their coffee, the meanings of the words have been expanding to accommodate the ever more international palate – buchta especially refers to a wider range of things than seen in the picture. Therefore, I still mess these words up constantly as I add new examples to my current understanding.

Exhibit B: Czech recipes: Banana bread, pound cake?

No self-respecting Czech person would truly refer to banana bread as bread (see exhibit A). Why isn’t it called cake?! I am asked. Instead, banana bread is a type of buchta in Czech – a serious blow to my idea that buchta always had filling – and the foreignness of the use of the word “bread” has to be clearly referenced in the recipe.

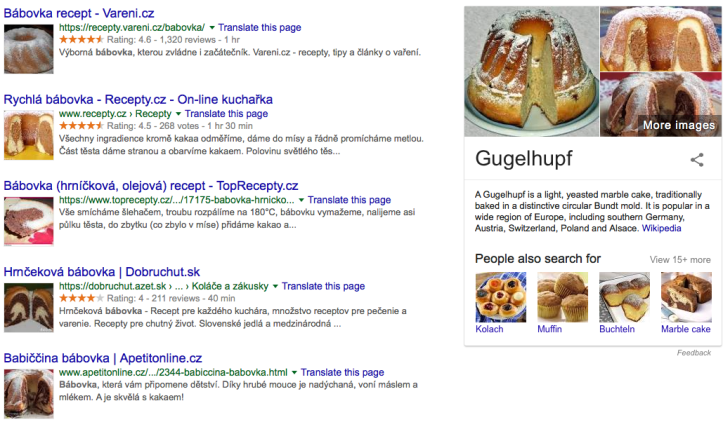

And bábovka – called marble cake, Bundt cake, or pound cake in English – also counts as buchta.

Fine, I give up. It’s clear to me now that buchta occupies some kind of weird middle ground as a (usually sweet) pastry you can eat as a somewhat substantial snack or with coffee but is not dessert, while dort (cake) is by definition dessert.

In conclusion? Just eat whatever they give you and don’t ask questions. Or just complain about it on your blog. Chleba, pečivo, buchta, koláč, or frgál are often baked by a professional Czech mom or grandma and they are simply bound to be delicious.

***

Czechs might be interested in the New York Times’ discussion of “kolach” as it has been brought by Czech immigrants to Texas. The Americans are having a tough time deciding where exactly it belongs… and as a result, are trying to claim it for themselves. (BIG RED FLAG! Americans love to claim things – it happened first with the lightning rod, which was obviously invented by Prokop Diviš and not Benjamin Franklin, and then with Budweiser. Don’t let it happen again!)

Readers from Slavic countries: Do you also have these issues in your language? Does the English perspective on bread, pastry, cake and pie confuse you?

[…] resisted – that every Czech meal is eaten with a side (potatoes, pasta, rice, dumplings, bread). We may do that in USA but mostly unintentionally (like how a hamburger has a bun). It surprised […]

LikeLike

[…] dish like potatoes, pasta, rice, or Czech bread or potato dumplings. Sometimes it’s sweet, like buchty or krupičná kaše, which is a semolina porridge with cocoa powder, sugar and melted butter on […]

LikeLike

[…] had hummus and baklava, mini tarts and mini bábovka, coffee-flavored mandlovice (an almond liquor) and Spanish oil with orange aroma. There were stands […]

LikeLike

[…] Meanwhile, I dressed as a babka, a Czech grandma character who carries a basket…with another grandma? Remember, just don’t ask questions. […]

LikeLike

As a native czech, I really enjoyed this article. I don’t want to be mean, but it is so funny.

But, we don’t have it easy when we are on holidays in the foreign country. I remember when I was in the shop abroad for the very first time – ”where are ‘rohlíky’?” and “THIS is ‘chleba’? 😀

And also – ‘chleba’ and ‘řízek’ (which is fried, usually chicken breast in flour, eggs and breadcrumbs) are typical food most czech people travel with.

We just love our bread 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can imagine how difficult it is! Based on your own travels, which country outside CZ has the best bread?

LikeLike

Well, Slovakia has their bread pretty good… but I think that it is just because it is very similar and Czech Republic and Slovakia used to be one state. 🙂

And I know that it isn’t bread like bread, but I absolutely love real french baguettes 🙂 ❤

LikeLike

See, that’s so funny, because for me baguettes are totally bread! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

The complexity Czech bread and baked goods can be reflected in buying flour here. You can throw any notions you have about “all purpose flour” out the window in a supermarket here. There are four main types to choose from, this article explains a bit the differences: http://whatsarahbakes.com/2015/11/01/czech-baking-ingredients/

Choice of flour makes a huge difference in the finished product. Many Czechs I know who have been to America and tried the American version of the “Kolachee” say it simply doesn’t cut it because all purpose flour was used instead of something more exacting.

That also goes a long way to explaining why Czechs are proud of their bread and miss it when they travel. It’s simply a more complex product.

LikeLike